As STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts/Humanities, and Math) continues to grow rapidly in the Informal Science Learning (ISL) Out-of-School-Time field, there exists a wide variety of STEAM findings from both researchers and practitioners. These findings are often developed in silos – research isolated from practice and practice from research. The Collaborative, in an initial informal study of this phenomenon, found that there was broad interest from both researchers and practitioners in bridging this gap, especially relating to equity in ISL. They demonstrated significant interest in developing ways to be aware of each other’s work and potentially to collaborate. To address this, Texas Southern University (TSU), one of the largest and most comprehensive HBCU’s (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) in the U.S., graciously partnered with the Collaborative. TSU, a long-time member of the Collaborative, is represented on the Collaborative Board of Directors by Bernnell Peltier-Glaze, Ed.D., Associate Professor, and on the Advisory Council by Lillian Poats, Ed.D., Professor and Former Acting Provost & Vice President for Academic Affairs & Research. Both are members of TSU’s Department of Educational Administration and Foundations in the College of Education. Dr. Peltier-Glaze, Dr. Poats, and Collaborative Executive Director Lucinda Presley developed this successful grant proposal. Dr. Poats is now the grant’s Principal Investigator (PI); Dr. Peltier-Glaze and Lucinda Presly are the Co-PIs. They are joined on the grant’s Leadership Team by Grant Advisor Judy Koke, Deputy Director and Director of Professional Learning at Institute for Learning Innovation, and by Grant Evaluator Kathy Terry, Senior Researcher at American Institutes for Research. This grant is a two-year (2023-2025) STEAM ISL working conference project that integrates a two-day in-person conference with two years’ virtual work by all participants. It addresses: 1) the need to develop more mutually supportive links between researchers and practitioners; 2) equitable access, framing, and design in STEAM ISL; and (3) through STEAM ISL, engaging underserved populations in STEM. The project accomplishes this by developing a cohesive approach, integrating research and practice to the most salient topics regarding equity, well-being, and belonging in STEAM ISL, with particular attention to where is the field now and the critical next steps that need to be taken. The project is also creating an effective model for a STEAM ISL working conference project to address equity, well-being, and belonging. Project participants will immerse themselves throughout these two years in equity, well-being, and belonging, choose and frame the seven most important topics to address, and investigate them through virtual and in-person convenings. The chosen topics are the result of a comprehensive literature review, surveys of the researcher/practitioner primary participants, and grant Advisory Council input. The topics, each of which are represented by an investigating cohort, are:

To investigate these topics in cohorts, 23 participants—leading researchers and practitioners from across the US who were part of the project development--will attend the In-person conference July 25-26 in Houston, TX, and work virtually with their cohort throughout this two-year project. Approximately another 50 participants will work with their cohort virtually the entire two-year period. Approximately 75 polled participants will complete several surveys about the topics throughout this project. The findings will then be consolidated and communicated to very broad and diverse audiences. The anticipated outcome of this project is a more cohesive view of STEAM ISL field is in relation to equity that will benefit a broad spectrum of underserved populations.

0 Comments

The Collaborative was recognized by the 88th Texas Legislature for its 10-year anniversary. The recognition was made possible by Cody Harris, Texas State Representative from District 8, in which the Collaborative is legally based.

The resolution noted the Collaborative’s contribution to education throughout the US. This contribution, it notes, applies its research-based focus on creativity and innovation through the intersections of Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts/Humanities, and Math (STEAM) in K-12 and lifelong learning.  The non-profit STEAM education organization, the Innovation Collaborative, has been awarded an anonymous $120,000 grant to build its infrastructure and expand its reach and visibility to education stakeholders throughout the country. The Collaborative provides information about how effective intersections of the STEAM subject areas—Sciences, Technology, Engineering, Arts/Humanities and Math—can reinforce creative and innovative thinking in K-12 and out of-school-time. STEAM is an approach to education that promotes student-led explorations driven by curiosity and the application of competencies and practices across academic disciplines that can effectively and equitably prepare them for success in education and the 21st century workforce. Now in its eleventh year, the Innovation Collaborative previously had been awarded multiple grants, including from the National Endowment for the Arts, to help them fulfill their mission of conducting and sharing STEAM-based research on teacher professional development and classroom practice across the recognized well-rounded subject areas. According to Executive Director Lucinda Presley, the new grant will enable the Collaborative to substantially expand its efforts to promote the value and purpose of STEAM education to a broader national audience. “I truly believe this award will help us reach decision-makers, educators, and parents who are interested in STEAM education but don’t necessarily understand how it can be effectively integrated into the curriculum of their schools’ and students’ daily learning.” The Collaborative’s Strategic Advisor Jonathan Katz, former Chief Executive Officer for the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies, pointed out that the organization has done a substantial amount of important work supporting rigorous STEAM focused research and identifying exemplary practices in the field. “The challenge,” he added, “is getting the word out to teachers and their leadership that we have resources to do this sort of teaching intentionally—that is, to bring the STEAM subject areas together in terms of instruction and evaluation and improve student learning in a holistic way that is both meaningful and valuable to their overall education.” Presley said the anonymous grant funds will be strategically applied over a three-year period and used to support a part-time staff that will be working to refresh the Collaborative’s website, raise its profile through social media and its newsletter, and establish opportunities for scholars and K-12 educators to propose STEAM-based new research and lessons that can be shared by the organization. For more information about the Innovation Collaborative visit https://www.innovationcollaborative.org/ and follow us on Facebook @innovationcollaborative.org, on X at #innovationcollaborative & LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/company/innov-collab/ The Importance of Failure

'Scientific American' features poem by Collaborative Strategic Advisor The October 2023 issue of Scientific American (Vol. 329, No. 3) features a poem by Innovation Collaborative board member and Strategic Advisor Jonathan Katz. Says Katz, “Poetry is a great medium for exploring the mysteries and ambiguities of human existence. As artificial intelligence enables large data bases, algorithms and bots to approach human senses of consciousness and individuality, a lot of fertile ground for poems emerges. AI propels both a perception of competition and a sense of solidarity between flesh-based and digital entities. Will bots enjoy poems? That remains to be seen, but a knee-jerk “no” in response to that question demonstrates the kind of hubris that gets humans in trouble. I find writing for an audience that includes digital entities a pretty interesting process and I think others who try it will find that as well.” C&R Press has published three collections of Katz’s poetry: Love Undefined, Objects in Motion, and Lottery of Intimacies. Click HERE to read the poem in Scientific American. NEUROSCIENCE: STRENGTHENING YOUR BRAIN Sandi Chapman, PhD Sandi Chapman, PhD Collaborative Research Thought Leader Sandi Chapman, PhD, and her institution, the UT Dallas Center for BrainHealth, invite you to participate in their Great Brain Gain challenge. You can access this challenge in their invitation below. Enjoy seeing how you can strengthen your brain. Our brain is one of the most modifiable parts of our body. Like our muscles, the brain can be strengthened over time. While many people know their brain can improve, they often don’t know what they can or should do to take action. Instead of focusing on decline, disease and doubt, Center for Brain Health is helping people everywhere feel empowered to improve and strengthen their brains’ fitness through daily, science-backed habits that make a difference. A simple first step to do this is to join the Center for BrainHealth’s 7-day Great Brain Gain text challenge, by texting GAIN to 888-844-8991. You’ll get daily tips to build brain-healthy habits in your everyday life. Here are 3 examples:

STEAM enthusiasts community The American Association for the Advancement of Science's (AAAS) discussion board for All Things STEAM (users must create a login to access the discussions) http://tinyurl.com/ykfjkmsn Progressive science education curriculum This book chapter abstract by Merrie Koester and Meta Van Sickle outlines how necessary the arts are for the fullest expression of any kind of learning, including and especially science. http://tinyurl.com/z82cesmf  The National Creativity Network The National Creativity Network engages, connects, informs, promotes, and counsels cross-sector stakeholders who skillfully use imagination, creativity, and innovation to foster vibrant and flourishing individuals, institutions, and communities across North America. Find out more on how to get involved and check out the article links on their blog. https://nationalcreativitynetwork.org/ Connecting STEAM to agriculture A University of Delaware program is equipping Delaware 4-H students with science, technology, engineering, arts, and math (STEAM) skills, and connecting them to agriculture. Twila Parish-Short, a 4-H youth development science educator with UD Cooperative Extension, is incorporating those five disciplines into educational programming and activities for children and teenagers around the state. She is developing a team of teenage ambassadors, as she calls them, to lead youth in STEAM education and activities. The hope, Parish-Short said, is for those ambassadors to bring the activities back to their communities, help young people explore their interest in STEAM fields, and broaden 4-H’s reach. “I’m envisioning these young STEAM ambassadors building their confidence to get into STEAM careers,” Parish-Short said. She recently hosted an event in for her first STEAM Team. Students formed groups to work on activities for this year’s 4-H STEM Challenge from the National 4-H Council. They were given projects on renewable energy that prompted them to choose an energy source to power a fictional bunker. Then, they built prototypes for those renewable energy sources using arts and crafts materials provided by Parish-Short. Read the full article HERE. Building science and engineering skills through STEAM The U.S. NAVFAC Northwest facility in Bothell, Washington, launched its Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) program, with an inaugural “Once Upon a STEAM” fairytale-themed Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math (STEAM) community event held at Woodside Elementary School this past November. Volunteers from NAVFAC Northwest joined a diverse array of participants, including public and private enterprises, collegiate academia, high school robotics programs, and coding companies, among others whose booths featured interactive but fast-paced STEM-related activities tailored for students in kindergarten through 5th grade. One of the most widely attended activities— the Parachute Community Build Contest—sparked creativity for participants by constructing parachutes to gain insights into the principles of gravity and aerodynamics. The event witnessed an impressive turnout, with both students and parents contributing to the creation of over 300 parachutes. Read the full article HERE. Fusing technology and creativity At Stony Brook (New York) University a collaboration between student and campus organizations aimed to bridge the gap between STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) and the arts, making technical fields more accessible and engaging for students of all majors. They launched their effort at an event, Hallo-STEAM, which featured three unique projects, each designed to showcase the fusion of technology and creativity that can be built by anyone even if they are not “tech-savvy.” “We have planned several events for elementary and high schoolers together that meld STEM and art (STEAM), specifically exploring how origami techniques can inspire engineering design. This event was therefore a natural progression for us and paired well with our goal of showcasing the interdisciplinary nature of STEM and art to audiences with little prior experience in STEM,” said Elizabeth Argiro, a biology major who heads the school’s Interactive Origami Club. The Hallo-STEAM event incorporated traditional origami, programming, and electronics. Attendees made flower vases with glowing origami tulips, lilies, and butterflies that lit up when you clap. According to Rachel Leong, president of Stony Brook’s, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, the program was a great opportunity to introduce circuits and coding to people who might not otherwise know much about it. “The combination of art and technology excites us, and we are thrilled to see more people interested in these fields,” she said. Read the full article HERE. Beetlejuice production partners with Dallas schools to teach STEAM skills Over the course of multiple weeks, 3,400 theatre students and teachers from 26 Dallas High Schools will participate in a specially created curriculum that connects to the Broadway Dallas production of Beetlejuice, the musical adaptation of Tim Burton’s film. Taught by Broadway Dallas teaching artists, as part of the lesson plan all the participating students and teachers will attend a dedicated performance of the musical, which runs February 20-March 3, 2024. The curriculum was developed to prepare students for college and 21st-century careers and includes a sequence of lesson plans where students will learn the art and science of hand drafting, which in the theater is used for scenic design. Through hand-drafting, students will apply basic principles of scales, measurement units, and physics, developing fundamental skills can be transferred to the construction, engineering, and architecture industries. Read the full article HERE. Winnipeg STEAM project INSPIRES young children Young Designers, a Winnipeg, Canada program, employs a trio STEAM support teachers who travel from school to school to provide a six-week program to nursery-to-Grade 2 students. Each 90-minute weekly session, which typically runs from 3:30 p.m. to 5 p.m., begins with free play and ends with a group dinner. Participants spend the bulk of the time in a group read-aloud and a related STEAM design challenge inspired by the week’s storybook. One assignment involved brainstorming about a fictional species and accompanying habitat. Chicoine’s youngest child came up with a creature who is half-dinosaur, half-gorilla and lives in a forest surrounded by an abundance of grass for the fantastic vegetarian to eat. During the 90-minute sessions, children and their caregivers play with light tables, robots, gear-building kits, pipe cleaners and geometric puzzles, among other crafty and constructible items that promote creativity and fine-motor skill development. The program received $500,000 via the province’s strengthening student support and learning grant program to get the extracurricular off the ground. Participating schools receive STEAM kits, books. and professional development. In addition to being fed, every family takes home a copy of the storybook of the week. Read the full article HERE. How the maker movement is changing education In Salt Lake City makerspaces are flourishing. Makerspaces are known as places where people, or “makers,” create, or “make,” projects using a variety of hands-on and digital tools. Commonly found at some libraries, museums, colleges and at places like the Utah STEM Action Center, the number of these spaces for open exploration have increased, especially in schools, which has given students equal access as well as gain skills in STEAM—science, technology, engineering, arts and mathematics. At the Utah Action Center, students have opportunities for hands-on making, creating, designing, and innovating that bring individuals together in a variety of mediums, including robotics, textile crafts, woodcrafts, and electronics. “Makerspaces need to be available and accessible,” said teacher Beth McKinney, who helped open the makerspace in Salt Lake’s Murray’s Hillcrest Junior High this fall. “It’s important for kids to have a place where they can explore their own interests, talents, curiosities and have that experience on their own with the freedom to do it in a safe, controlled setting. Many students might not have the tools, the confidence, or the opportunity to do so, so it’s important we have a safe space where any student can create and many learn best by doing, with their own hands.” Read the full article HERE. creating innovation challenges for students The purpose of science competitions or science fairs in STEM education is to provide students with opportunities to experience and practice science as it is practiced and experienced in the real world. A Framework for K–12 Science Education argues that the principal aim of science is to create and critique evidence-based causal accounts of natural phenomena (NRC 2012). To support this, the Next Generation Science Standards have outlined “science practices” as a guide for reproducing authentic science learning in the classroom (NGSS Lead States 2013). Further, the Frameworks suggests that science progresses through discourse within the community of scientists and emphasizes that students should learn to communicate and argue about information and findings "clearly and persuasively" (NRC 2012 p. 53). So, how can authentic science experiences be supported in classrooms? To answer that question the independent research-based non-profit TERC, has created the Innovate to Mitigate project, which hosts open innovation challenges nationally for young people ages 13–18 to develop methods for mitigating global climate change. Past submissions have included projects in a wide range of domains (e.g., energy conservation, alternative energy generation, agricultural methods, or social/behavioral change). Read the full article HERE. Providing culturally relevant STEM pedagogy The Noyce STEM INSPIRES program, a collaboration between West Oso ISD, Texas A&M Corpus Christi, and the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP). Texas A&M Corpus Christi, focused on providing secondary STEM teachers culturally relevant pedagogy for diverse student populations. The main goal of the NSF Noyce Scholarship program is to recruit, train, prepare, and retain highly effective elementary and secondary mathematics and science teachers (i.e., Noyce Scholar undergraduate teacher candidates) and teacher leaders in high-needs districts. Students participate in educational experiences that implement critical service-learning projects, reinforcing STEM grades 7–12 education for underrepresented groups in high-needs schools. Critical service learning is different than traditional service learning with its three-pronged approach. The community learning component provides experiences with community mentors, and university faculty with the Noyce INSPIRES team including West Oso ISD teachers. The program emphasizes the power of community and forge relationships between school district stakeholders, teacher candidates, and key community members for teacher candidates to become agents of change in their communities. In the first year of the grant, the Noyce INSPIRES team was able to partner with the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) and the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History on a critical service-learning project benefiting the entire community. A local teacher who was a former director of educational activities for the IODP’s Deep Earth Academy was instrumental in bringing the NSF-funded, pop-up science exhibit In Search of Earth’s Secrets to West Oso ISD. The teacher worked aboard the IODP research vessel, JOIDES Resolution. The project intentionally requires the exhibit to travel to an accessible community site. Read the full article HERE. The Collaborative newsletters have been featuring conversations among its Research Thought Leaders, who are nationally and internationally recognized experts in their respective fields of arts, sciences, creativity, and neuroscience. These conversations provide robust insights into the importance of creative (a novel idea) and innovative (applying the novel idea to solve a problem) thinking. This article builds on those insights to offer a look at how creative and innovative thinking could be used in K-12 classrooms. In the following articles, we will look at how curriculum could change to provide these important skills, what administrators need to know about them, and why we should care about STEAM, which fosters these skills. We invited the Collaborative’s Innovation Fellows to offer their perspectives. The Fellows are top K-12 arts, STEM, and classroom teachers and administrators from across the U.S. who help lead the Collaborative’s K-12 STEAM efforts. Charles Hayes, formerly a 5th grade science teacher, is advisor for middle school science in Memphis-Shelby County schools. Anne Ludes, a graduate of the Collaborative’s STEAM Teacher/Administrator Professional Development program, is Director of the Massachusetts Academy of Math and Science at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Ashley Lupfer is K-8 Visual Arts Educator at Brooke Charter Schools in Boston, MA. Kimberly Olson is Visual Arts Educator at Centre School in Hampton, New Hampshire. Julie Olson, formerly a high school science teacher, is now Natural Science Instructor at Southeast Technical College in Sioux Falls, SD. Kathleen Sweet, former elementary school Art Educator, is now Student Improvement Coordinator and Computer Science Teacher (grades 2-5) for Starmont Community School District, IA. Below are questions and valuable insights from these educators and administrators. 1. How could/do you use creative thinking in STEAM in your classroom, school, or work environment? Charles Hayes One of my responsibilities as the middle school science advisor in my district is to develop curriculum that allows instructors to encourage creativity and innovation in the pupils. As a result, I rely on guidance presented in A Framework for K-12 Science Education: Practices, Crosscutting Concepts, and Core Ideas (2012), which suggests that the best to way to teach science is to construct lessons around science and engineering practices, crosscutting concepts, and disciplinary core ideas. “The science and engineering practices mentioned in this work and the Collaborative’s Effective Practices Higher-Level Thinking Skills have a lot of commonalities.” My intentionality in lesson planning for our teachers, based on lessons that best support and highlight these skills, ensures that they have the resources, plans, and support they need to engage our children in meaningful hands-on experimental and project-based activities that shift away from rote memory assignments and toward activities that allow them to be creative, develop soft skills, and improve their scientific literacy. A lot of our lessons require students to create new ways of looking at existing phenomena. We challenge them to come up with different approaches to explaining the phenomena and new ways to test ideas and also to generate new ideas and thought-provoking questions based on their findings. We use statements such as “What if…, I wonder what would happen if…, Is there a different way…”. Anne Ludes Our teachers constantly redesign their units to make sure the content is fresh and relevant to our students. This means analyzing data and incorporating feedback so the students get as much out of their work as possible. Nearly everything we do is project- or inquiry-based. “This allows our teachers to start their lesson planning with "What if I do this instead?" as the way they prepare for an upcoming unit.” Everyone collaborates with each other, so teachers bounce ideas off everyone else—me as the director, the school counselor, other teachers, and the students - to work out the details. And this philosophy is at the heart of our school culture: Think creatively, reinvent yourself, take risks, and stretch yourself to grow as much as you can! Our Humanities teacher delivers a lesson on Tom Stoppard's Arcadia (a brilliant play that I highly recommend if you haven't read it already!) and integrates the concepts of entropy, fractals, and chaos theory into her instruction (co-taught by a me, a former math teacher and now director of the program). The students' reflections and final projects are all unique and creative representations of their understanding of these concepts. Some projects take the form of a poem, a musical composition, a computer program, or even a board game. Julie Olson In the sciences, there are so many abstract ideas (e.g. the atom) that students need to be able to visualize in their heads. Space, color, and arrangement all help to "arrange" the parts of these not really seen entities. I give students a variety of materials when doing projects - the more the better. Sometimes/oftentimes they are initially overloaded, but then categorize, visualize, and start to put some of these things together in their heads before actually testing and building. “My Physics students do the Art and Light project with the addition of describing the physics of their projects (e.g. reflection, wavelength, color) as well as the biology of vision. They have to make their projects in this unit aesthetically pleasing and engaging.” They also create marble runs at the end of the semester with requirements taken from the various units (e.g. waves, potential and kinetic energy). Environmental Science discusses the aesthetics of good conservation. The students have many open-ended experiments that require them to visualize, assemble, and communicate their findings in graphs, charts, and diagrams. Anatomy and Physiology classes are tasked with creating an assist device for someone that cannot grasp a pen, pencil, marker, or paintbrush so they can use it in art class. The device must be comfortable, look good, and appeal to a young pre-teen. Kimberly Olson Creative thinking is the very basis of my entire elementary curriculum. “Students respond to open-ended lesson problems to apply the design thinking process which so closely mirrors the science inquiry process.” Students apply lesson objectives as “I Can” statements derived from the standards to formulate their own individual responses. Some responses may lead to collaboration, innovation, and extended learning. Social emotional learning is supported throughout and contributes to perseverance, autonomy, and grit. Student artists are observers, observing and asking questions. They also visually analyze, define, and clarify a problem, shift between perspectives based on discipline connections, and make connections to their own interests in order to generate ideas to develop solutions. Along the way they communicate in a variety of ways, collaborate, persist, and assist as necessary to an end based on a rich and inspired journey. Kathleen Sweet You can use creative thinking in every subject, classroom, or work environment. “This type of thinking promotes engagement and keeps things moving forward, not becoming stagnant.” An example: Co-teaching with the art, science, and language arts teachers. Using bacteria to paint original art and using writing to communicate and explain your thoughts and ideas. You would be learning about science, art, and writing and developing all those skills simultaneously. 2. How could/do you use innovative thinking in STEAM in your classroom, school, or work environment? Charles Hayes “Our district recognizes the value of Project-Based Learning (PBL) in developing our kids’ inventive abilities.” We are planning several science competitions in which students will consider local, regional, and national issues and research related to these issues. Students will develop innovative and novel approaches to addressing these issues based on information and thinking skills developed in our classrooms. Ashley Lupfer “Providing students time in the classroom to create and innovate is essential.” Time to understand a problem, to experiment with new tools and materials, and to work with their peers to develop original ideas. When students are learning within a culture of creativity, they have time to become more invested in the learning, are more comfortable expressing their ideas, and are more open to taking risks. In my classroom, activities often provide a balance of choice and structure. Anne Ludes “Our program is all about innovative thinking!” For example, our students' first project in their computer science class is to use HTML and CSS to develop their own websites from scratch! They have to think about color (RGB), formatting, design, images, organization and layout, as well as content. And their final products are BEAUTIFUL and informative. But it doesn't stop there! In their STEM class, our students put their engineering design skills to good work when they develop and build an assistive device to help a client in need. The students have to work collaboratively to address a person's disability while thinking about utility, cost of materials, and the person's individual needs. Students use so many of their higher-level thinking skills, including defining a problem, generating and evaluating ideas, synthesizing, developing a solution, and persisting. And all the while they also are becoming more aware of the lives of others. Julie Olson More open-ended experiments and engineering projects. Student choice is necessary. Kimberly Olson Students approach all problem-solving aspects of lessons secure in the knowledge that “there are no mistakes in Art.” They work to imagine and develop their own personal responses to lesson problems and often, serendipitously, their work transcends creativity to elements of innovation. This occurs through collaborative work at the elementary level as well. Creating a safe, student-reflective curriculum, classroom community, and learning environment establishes the climate students need to feel able to take risks, revise, share, and elaborate or extend ideas and learning. “Basing learning on student interest and identity establishes the right conditions for creativity to move closer toward innovative thinking and doing.” Kathleen Sweet “I believe that giving open-ended directions or parameters with enough direction to start with an idea but end up with a new one helps to promote innovative thinking.” An example: To pair up two or more people and give them a piece of paper, 12 inches of tape, and scissors. Then ask them to make something using these materials. The outcomes would be infinite, even though every group received the same materials and directions. Thanks to our esteemed Innovation Fellows for sharing their insights and especially for their creative and innovative efforts that inspire us all. what is steam to you? In education, STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) is a rapidly growing strategy in many learning settings. In can be found in K-12 classrooms, in museums and other out-of-school-time venues, in higher education, and even in educational toy product development. In practice, STEAM takes many different forms. It accomplishes different goals, depending on its usage. The Innovation Collaborative’s STEAM goals are to provide a strong research base for STEAM effective practices in K-12 and out-of-school-time experiences, lessons, and strategies. The Collaborative also is focused on effective collaboration across disciplines and learning settings. In this role, the Collaborative is interested in how others perceive STEAM.

Join us in this quest to understand STEAM more deeply by sharing YOUR ideas of what STEAM is. Answer any or all of the above questions. You can respond briefly or in depth, but please limit your response to 300 words or less. To get a start on your answers to the above questions, review the Collaborative’s position on STEAM at http://www.innovationcollaborative.org/steam-position.html Click on this link or use the QR code to respond. perceptions of steam As we look at perceptions of STEAM in this newsletter issue, it is helpful to look at some of the work that already has been done to understand the many lenses through which STEAM is perceived. Important work in this area has been done by the Arts Education Partnership (AEP). A national network of organizations that helps advance arts education, AEP focuses on research, policy, and practice. Below are some STEAM policy briefs that AEP has produced. Preparing Students for Learning, Work and Life. P-5 STEAM Education and Equity. Research and Policy Implications of STEAM Education for Young Students. Who’s Who in STEAM Education and State Governance.  By David Pyle, Collaborative Advisory Council member* "I'm very concerned that the visual thinking mind - the art mind — is being screened out of school,” said Dr. Temple Grandin during a rapid-fire widely broadcast interview hosted as a partnership between the Colorado State University Arts Management program and the International Art Materials Trade Association (NAMTA). On February 23, I had the pleasure and privilege of hosting this special Zoom-based conversation with Dr. Grandin as she discussed the principles in her new book, Visual Thinking; The Hidden Gifts of People Who Think in Pictures, Patterns, and Abstractions. In her book — and during the Zoom-based program - she repeatedly emphasized the critical importance of learning in the arts — not just for their standalone value — but also for their impact in cultivating skills for which our larger communities and economy have a direct and dramatic need. "We're seeing a gigantic shortage in the skilled trades — and those are where we need the art mind," she said. Dr. Grandin is a professor of animal science at Colorado State University and the author of New York Times bestsellers Animals in Translation, Animals Make us Human, The Autistic Brain and Thinking in Pictures, which became an HBO movie starring Claire Danes. "When I was a child, art was my absolutely favorite class. Art and mechanics go together," noted Dr. Grandin. "(But now) we've got too many kids who have never done any art. Who have never used any tool. We are losing skills! We've lost the clever fixers!" She also cites sewing as a powerful skill-building tool. "I sewed costumes for the school play. I was not interested in being IN the school play. I wanted to make costumes FOR the school play." In her book, Visual Thinking, Dr. Grandin adds, "We screen out designers, inventors, and artists. We need future generations who can build and repair infrastructure, overhaul energy and agriculture, create tools to combat climate change and pandemics, develop robotics and AI. We need people with the imagination to invent our next-generation solutions." (Visual Thinking, p. 55) As further evidence of the need for arts experiences, she noted that "Nobel prize winners are 50% more likely to have an arts and craft hobby compared to other scientists." (Robert Root Bernstein et.al. 2008) As the session approached its close, I asked her, "You've made such a strong and compelling case for hands-on arts education, how can we move past preaching to the choir? How can we advocate for arts education to the larger community?" She quickly answered, "I think we have to do it one school district at a time. And then we need to write about it." *David Pyle is an artist and Instructor in the Colorado State University Arts Management program in addition to being Creative Director of Pyle Creative Studio. He is known for his 35-year career in the art products business. There he most recently was Senior Vice President/Group Publisher for F+W Media, managing The Artist’s Magazine, American Artist, Watercolor Artist, Interweave Knits, Love of Quilting, and more. He is author of What Every Artist Needs to Know About Paints and Colors. Free Summer Virtual STEAM Professional Development for Public School K-12 Teachers |

| Melissa Collins | Charles Hayes | Anne Ludes | Carla Neely |

The Innovation Collaborative is proud to announce new Innovation Fellows who have been invited by the Board of Directors to join the Collaborative’s work in K-12.

Innovation Fellows are top K-12 administrators and arts, STEM, and classroom teachers from across the US who are influential STEAM advocates. They are the planning team who help lead the Collaborative’s K-12 Effective Practices project that focuses on classroom practices and teacher professional development.

The Collaborative’s initial Fellows were identified in the first round of national K-12 STEAM research. Additional fellows are invited to join this group, based on their impressive abilities to move the K-12 STEAM field forward through teaching and administration.

These new Fellows are impressive in their own right.

Innovation Fellows are top K-12 administrators and arts, STEM, and classroom teachers from across the US who are influential STEAM advocates. They are the planning team who help lead the Collaborative’s K-12 Effective Practices project that focuses on classroom practices and teacher professional development.

The Collaborative’s initial Fellows were identified in the first round of national K-12 STEAM research. Additional fellows are invited to join this group, based on their impressive abilities to move the K-12 STEAM field forward through teaching and administration.

These new Fellows are impressive in their own right.

- Melissa Collins has been an active member of the Collaborative’s Advisory Council since 2020. She teaches second grade at John P. Freeman Optional School, an underserved school in Memphis, TN. There, she emphasizes curiosity in science and is a teacher leadership expert. Melissa has won numerous awards, including the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science and Math Teaching, the National Science Teaching Association's (NSTA) Sylvia Shugrue Award for elementary teachers, and in 2020 was named to the National Teacher Hall of Fame.

- Charles Hayes has been the fifth grade science lead at a Title 1 School in Memphis TN for nine years. This year he is serving as instruction advisor for middle school science in the Memphis-Shelby County Schools’ Department of Curriculum and Instruction. He has won a number of awards, including the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science and Math Teaching and the National Science Teaching Association’s (NSTA) Shell Science Teacher Award. Charles embraces STEAM and the Collaborative’s work.

- Anne Ludes is a spring, 2021, graduate of the Collaborative's STEAM Professional Development (PD) and became a leader in planning our subsequent STEAM PDs. She was Assistant Superintendent for Secondary Education at Framingham Public Schools, MA, and is now Director of the Massachusetts Academy of Math and Science at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, MA. She is passionate about the Collaborative's approach to STEAM. She said, "This work has been absolutely game-changing for me... As an administrator, this project has been instrumental in helping me develop the language and depth of understanding necessary to support teachers with curriculum development, lesson planning, and instructional practices.”

- Carla Neely has been teaching fifth and sixth grade science at an African American all-girls school, Warner Girls Leadership Academy, in Cleveland, Ohio. She was one of 15 teachers across the US selected as 2022-23 Albert Einstein Distinguished Educator Fellows. As an Einstein Fellow, she is working as a STEM Legislative Fellow in a Nevada Senator's office in DC, developing ways to make STEM more equitable for girls of color, which is her specialty. Before her selection as an Einstein Fellow, she taught STEAM in her science classroom and developed a STEAM lab. She also conducted research regarding equity for girls in STEM.

How do research and perspectives on imaginative thinking in STEM education and practice relate to STEM learning in museums? That was an important question asked by the Museum of Science (MOS), Boston, in a project funded by the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Advancing Informal STEM Learning (AISL) program.

To address this question, the MOS team, led by Becki Kipling, Principal Investigator, and Christine Reich and Sarah May, Co-Principal Investigators, brought together researchers, practitioners, educators, and others for a series of convenings. There were rich conversations about imagination between Informal Science Education (ISE) professionals and between ISE professionals and those from other domains. The Collaborative was included in these convenings. Many important insights were gained.

Enriching this work are a recently released literature review, a survey of ISE professionals, and a number of other products related to this topic. These can help identify and stimulate future areas of research.

See these rich Museum of Science, Boston resources to learn more about the convening’s proceedings, a framework for defining imagination in STEM, and a number of other important resources. You can find project descriptions from 25 unique projects that use imagination in a variety of ways in the Project Index. You can find the YouTube playlist at Unpacking the STEM Imagination Convening YouTube Playlist.

See also the Research Thought Leader article in this newsletter where the Collaborative’s Science Thought Leader, Hubert Dyasi, PhD, and its Arts Thought Leader, Rob Horowitz, EdD, discuss how creative thinking (which includes imagination) bridges the science and the arts.

To address this question, the MOS team, led by Becki Kipling, Principal Investigator, and Christine Reich and Sarah May, Co-Principal Investigators, brought together researchers, practitioners, educators, and others for a series of convenings. There were rich conversations about imagination between Informal Science Education (ISE) professionals and between ISE professionals and those from other domains. The Collaborative was included in these convenings. Many important insights were gained.

Enriching this work are a recently released literature review, a survey of ISE professionals, and a number of other products related to this topic. These can help identify and stimulate future areas of research.

See these rich Museum of Science, Boston resources to learn more about the convening’s proceedings, a framework for defining imagination in STEM, and a number of other important resources. You can find project descriptions from 25 unique projects that use imagination in a variety of ways in the Project Index. You can find the YouTube playlist at Unpacking the STEM Imagination Convening YouTube Playlist.

See also the Research Thought Leader article in this newsletter where the Collaborative’s Science Thought Leader, Hubert Dyasi, PhD, and its Arts Thought Leader, Rob Horowitz, EdD, discuss how creative thinking (which includes imagination) bridges the science and the arts.

The Collaborative recently participated as a Community Partner in the highly successful BrainHealth Week sponsored by the University of Texas at Dallas Center for BrainHealth.

Held February 20-24, BrainHealth Week was a free of charge five-day interactive event where people of all ages were shown how to build habits that promote a healthier brain and improve the trajectory of their lives. This included both in-person and virtual experiences with expert speakers, engaging activities, and access to brain health habits that can become part of one’s daily routine.

The Center for BrainHealth’s Chief Director, Sandi Chapman, PhD, is the Collaborative’s Neuroscience Research Thought Leader who, along with three other Thought Leaders, help lead the Collaborative’s work conceptually. Through Sandi, the Collaborative’s work centers on vital research-based thinking skills that the Collaborative shares with students and teachers across the US.

According to the Center for BrainHealth, “cognitive neuroscience suggests that the trend of worsening brain outcomes, such as decline, disease, mental health disorders, despair, loneliness, and brain fog can be reversed. Healthier brain habits can change this. Intelligence, memory, cognitive function, and even mental health can be impacted by how we protect and train our brains. In a groundbreaking study of 187 adults of all ages, 80% saw an improvement in their BrainHealth index scores (a scientifically validated measure the of the brain’s holistic health and fitness). Participants who engaged the most with proactive brain health strategies experienced the largest gains.”

The cognitive neuroscience conducted at the Center for BrainHealth and other leading research institutes around the world clearly demonstrates that our brain’s health and performance can be affected by daily, proactive practices. When talking about Brain Health Week, Sandi said, “At the Center for BrainHealth, we are uniquely devoted to discovering and applying the latest scientific findings about the brain’s ability to change based on how we use it.” She added, “What good is science if people don’t know how to use it to make their lives better”?

You can find out more about how you can maximize your brain’s capacities at BrainHealth.

Held February 20-24, BrainHealth Week was a free of charge five-day interactive event where people of all ages were shown how to build habits that promote a healthier brain and improve the trajectory of their lives. This included both in-person and virtual experiences with expert speakers, engaging activities, and access to brain health habits that can become part of one’s daily routine.

The Center for BrainHealth’s Chief Director, Sandi Chapman, PhD, is the Collaborative’s Neuroscience Research Thought Leader who, along with three other Thought Leaders, help lead the Collaborative’s work conceptually. Through Sandi, the Collaborative’s work centers on vital research-based thinking skills that the Collaborative shares with students and teachers across the US.

According to the Center for BrainHealth, “cognitive neuroscience suggests that the trend of worsening brain outcomes, such as decline, disease, mental health disorders, despair, loneliness, and brain fog can be reversed. Healthier brain habits can change this. Intelligence, memory, cognitive function, and even mental health can be impacted by how we protect and train our brains. In a groundbreaking study of 187 adults of all ages, 80% saw an improvement in their BrainHealth index scores (a scientifically validated measure the of the brain’s holistic health and fitness). Participants who engaged the most with proactive brain health strategies experienced the largest gains.”

The cognitive neuroscience conducted at the Center for BrainHealth and other leading research institutes around the world clearly demonstrates that our brain’s health and performance can be affected by daily, proactive practices. When talking about Brain Health Week, Sandi said, “At the Center for BrainHealth, we are uniquely devoted to discovering and applying the latest scientific findings about the brain’s ability to change based on how we use it.” She added, “What good is science if people don’t know how to use it to make their lives better”?

You can find out more about how you can maximize your brain’s capacities at BrainHealth.

Crayola Creativity Week

Crayola recently held its highly successful Creativity Week. It engaged 3.5 million children and 195,000 teachers in 77 countries.

In talking about Creativity Week, Crayola Director of Education, Cheri Sterman, said, “At Crayola Education we strive to give children, educators, and parents resources and inspiration to help them create and learn, opening their imaginations so they can pursue their dreams. Within Crayola Creativity Week, we collaborated with many organizations and creative spokespersons to inspire kids around the world, including NASA, Penguin Random House, HarperCollins Publishers, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, KIDZ BOP, GoNoodle, Khan Academy Kids, National Art Education Association, American Association of School Librarians, World Reader, Code.org, and the YMCA. Getting the word out about the power of creativity to help kids learn was a major objective of the celebration. Crayola is thrilled that the public tuned in to this message, with 615 million media impressions!”

Celebrity presenters included astronaut Ricky Arnold, who started his career as a middle school science educator and told kids how he needed creative thinking to be both a teacher and an astronaut, and Today Show meteorologist Dylan Dreyer, who talked about how creativity has been the guiding force in all her career decisions.

Visit the Creativity Week website for a wealth of teacher and parent resources. These include videos, read alongs, Thinking Sheets, creative challenges, and more.

Crayola recently held its highly successful Creativity Week. It engaged 3.5 million children and 195,000 teachers in 77 countries.

In talking about Creativity Week, Crayola Director of Education, Cheri Sterman, said, “At Crayola Education we strive to give children, educators, and parents resources and inspiration to help them create and learn, opening their imaginations so they can pursue their dreams. Within Crayola Creativity Week, we collaborated with many organizations and creative spokespersons to inspire kids around the world, including NASA, Penguin Random House, HarperCollins Publishers, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, KIDZ BOP, GoNoodle, Khan Academy Kids, National Art Education Association, American Association of School Librarians, World Reader, Code.org, and the YMCA. Getting the word out about the power of creativity to help kids learn was a major objective of the celebration. Crayola is thrilled that the public tuned in to this message, with 615 million media impressions!”

Celebrity presenters included astronaut Ricky Arnold, who started his career as a middle school science educator and told kids how he needed creative thinking to be both a teacher and an astronaut, and Today Show meteorologist Dylan Dreyer, who talked about how creativity has been the guiding force in all her career decisions.

Visit the Creativity Week website for a wealth of teacher and parent resources. These include videos, read alongs, Thinking Sheets, creative challenges, and more.

STEAM Imagination

By Merrie Koester, PhD, Collaborative Advisory Council Member

Pre-pandemic, I received a surprising email from education researcher, philosopher, and editor Dr. David Flinders: Dear Dr. Koester, You have been invited to submit a commentary for Routledge Encyclopedia of Education. I would be grateful if your commentary were entitled "Science Curriculum." To say I was stunned by the invitation would be an understatement. First of all, the challenge to write an encyclopedia entry of any kind implied I had the authority to do so. Does anyone? I also recalled believing as a child that the World Book Encyclopedia was a Great Repository of Truth. And then I reflected on the problem of names and the energy of language. To name something is to stake a claim of knowing its signification. This is a responsibility the Innovation Collaborative has not taken lightly as we’ve labored over what we “mean” when we say STEAM, creativity, innovation, transdisciplinary, etc.

Next, I thought about how this this human endeavor we call Science is not about getting things right, but rather about getting them less wrong, using the best evidence available to one at the time. Similarly, the Innovation Collaborative’s work—the research and the practices—don’t just tell what STEAM is, they SHOW how STEAM thinks and performs!

Next, I thought about how this this human endeavor we call Science is not about getting things right, but rather about getting them less wrong, using the best evidence available to one at the time. Similarly, the Innovation Collaborative’s work—the research and the practices—don’t just tell what STEAM is, they SHOW how STEAM thinks and performs!

As background, I was invited to present a paper at the 2016 American Educational Research Association (AERA) conference for a session called Eisner in Mind: Fresh Perspectives on Inquiry and Education. During my talk, entitled “Imagination and the Arts as Antidotes for STEM Education Malaise and Alienation”, I recalled scientist James Trefil’s writing about “The Great Turn Off” to school science, a disheartening event that occurs sometime around middle school and which Trefil attributed to a near total lack of creativity in traditional science teaching. I didn’t need to convince this room of creatives at AERA that something needed to be done! Like Trefil, I lament the dire consequences of a science illiterate nation.

Making science accessible and meaningfully engaging to all students is an ill-structured problem at best, one beset with issues of power, culture, and privilege, and the ever-present requirement that students meet performance benchmarks on content knowledge standards. When a science class is named a STEAM studio, students get to see that the very act of doing science requires a curious, creative mind and heart. Through noticing, listening, attending, and personal story-making – leaning in – science learning begins to matter.

And so I accepted the challenge from Routledge, but respectfully asked (and was approved) to change the entry’s title to “Progressive Science Education Curriculum.” I also asked if my colleague, Dr. Meta Van Sickle, might join me as a thought partner. Between us, Meta and I have devoted over sixty years to the research and practice of “Science Curriculum” as a “creative making practice”, decades before anyone named STEAM as educational practice. In 2018, Meta and her colleague, Dr. Judith Batzler, working with IGI, edited Cases on STEAM Education in Practice, to which I also contributed.

Gradually, the work for Routledge progressed, in just the same messy, organic way that all creative making requires. During the pandemic, the publishers themselves got creative with the platform, deciding to launch the project under a new name, Routledge Resources Online — Education, in order to better describe the scope of the product and to pivot to an increasingly virtual, post-pandemic world of readers. And now, I’m happy to share that at long last, Progressive Science Education Curriculum has been published! Being part of this incredible collective called the Innovation Collaborative has fueled my hope that we may have finally arrived at a time when we can design and put into practice truly educative and progressive models that provide joyful time and space for creative making and thinking. The Collaborative outreach/research is providing strong evidence to support the claim that STEAM learning experiences, those that are inclusive, empowering, emergent, and creative — not just numbers-based, procedure-driven, and geared toward mastery of knowledge that will be on a test — matter! Just STEAMagine where we’ll go from here!

Merrie Koester, Ph.D.

Science Literacy, Communication, and STEAM Curriculum Specialist

University of SC Center for Science Education

Founder, Director, Kids Teaching Flood Resilience

By Merrie Koester, PhD, Collaborative Advisory Council Member

Pre-pandemic, I received a surprising email from education researcher, philosopher, and editor Dr. David Flinders: Dear Dr. Koester, You have been invited to submit a commentary for Routledge Encyclopedia of Education. I would be grateful if your commentary were entitled "Science Curriculum." To say I was stunned by the invitation would be an understatement. First of all, the challenge to write an encyclopedia entry of any kind implied I had the authority to do so. Does anyone? I also recalled believing as a child that the World Book Encyclopedia was a Great Repository of Truth. And then I reflected on the problem of names and the energy of language. To name something is to stake a claim of knowing its signification. This is a responsibility the Innovation Collaborative has not taken lightly as we’ve labored over what we “mean” when we say STEAM, creativity, innovation, transdisciplinary, etc.

Next, I thought about how this this human endeavor we call Science is not about getting things right, but rather about getting them less wrong, using the best evidence available to one at the time. Similarly, the Innovation Collaborative’s work—the research and the practices—don’t just tell what STEAM is, they SHOW how STEAM thinks and performs!

Next, I thought about how this this human endeavor we call Science is not about getting things right, but rather about getting them less wrong, using the best evidence available to one at the time. Similarly, the Innovation Collaborative’s work—the research and the practices—don’t just tell what STEAM is, they SHOW how STEAM thinks and performs!

As background, I was invited to present a paper at the 2016 American Educational Research Association (AERA) conference for a session called Eisner in Mind: Fresh Perspectives on Inquiry and Education. During my talk, entitled “Imagination and the Arts as Antidotes for STEM Education Malaise and Alienation”, I recalled scientist James Trefil’s writing about “The Great Turn Off” to school science, a disheartening event that occurs sometime around middle school and which Trefil attributed to a near total lack of creativity in traditional science teaching. I didn’t need to convince this room of creatives at AERA that something needed to be done! Like Trefil, I lament the dire consequences of a science illiterate nation.

Making science accessible and meaningfully engaging to all students is an ill-structured problem at best, one beset with issues of power, culture, and privilege, and the ever-present requirement that students meet performance benchmarks on content knowledge standards. When a science class is named a STEAM studio, students get to see that the very act of doing science requires a curious, creative mind and heart. Through noticing, listening, attending, and personal story-making – leaning in – science learning begins to matter.

And so I accepted the challenge from Routledge, but respectfully asked (and was approved) to change the entry’s title to “Progressive Science Education Curriculum.” I also asked if my colleague, Dr. Meta Van Sickle, might join me as a thought partner. Between us, Meta and I have devoted over sixty years to the research and practice of “Science Curriculum” as a “creative making practice”, decades before anyone named STEAM as educational practice. In 2018, Meta and her colleague, Dr. Judith Batzler, working with IGI, edited Cases on STEAM Education in Practice, to which I also contributed.

Gradually, the work for Routledge progressed, in just the same messy, organic way that all creative making requires. During the pandemic, the publishers themselves got creative with the platform, deciding to launch the project under a new name, Routledge Resources Online — Education, in order to better describe the scope of the product and to pivot to an increasingly virtual, post-pandemic world of readers. And now, I’m happy to share that at long last, Progressive Science Education Curriculum has been published! Being part of this incredible collective called the Innovation Collaborative has fueled my hope that we may have finally arrived at a time when we can design and put into practice truly educative and progressive models that provide joyful time and space for creative making and thinking. The Collaborative outreach/research is providing strong evidence to support the claim that STEAM learning experiences, those that are inclusive, empowering, emergent, and creative — not just numbers-based, procedure-driven, and geared toward mastery of knowledge that will be on a test — matter! Just STEAMagine where we’ll go from here!

Merrie Koester, Ph.D.

Science Literacy, Communication, and STEAM Curriculum Specialist

University of SC Center for Science Education

Founder, Director, Kids Teaching Flood Resilience

Best STEM Books for 2022

In fall 2022, representatives from the National Science Teaching Association’s Children’s Book Council and from other disciplinary groups met for the sixth time to select exemplary children’s literature in STEM.

Since 2014 this joint committee has sought out literature that represents the best of STEM through:

It’s important to note that the criteria above do not require science content—even if it is integrated across disciplines. The best STEM books might represent the practices of science and engineering by:

Some of these books might not cover STEM content at all. They might simply define STEM habits of mind. For example, a biography might be STEM if it shows creative thought, progressive improvement, and even struggle and failure. But just telling a sequential story of achievement in a biography would not make it a STEM book. A winner would have to provoke a sense of innovation in the reader in any genre.

All the winners are interdisciplinary in some way: Content, process, and field of endeavor. The list below attempts to classify them, but, of course, the greatest STEM achievements defy classification.

Biographies

Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Golda Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer

Traci Sorell

Building Zaha: The Story of Architect Zaha Hadid

Victoria Tentler-Krylov

A Life Electric: The Story of Nikola Tesla

Azadeh Westergaard

Benoit Mandelbrot: Reshaping the World

Robert Black

Secrets of the Sea: The Story of Jeanne Power, Revolutionary Marine Scientist

Evan Griffith

Thank You, Dr. Salk!: The Scientist Who Beat Polio and Healed the World

Dean Robbins

The Stuff Between the Stars: How Vera Rubin Discovered Most of the Universe

Sandra Nickel

Wonder Women of Science: Twelve Geniuses Who Are Currently Rocking Science, Technology, and the World

Tiera Fletcher and Ginger Rue

Inventions

Awards also were given to books about inventions and the process that multiple inventors went through.

Bicycle: Eureka! The Biography of an Idea

Lori Haskins Houran

Light Bulb: Eureka! The Biography of an Idea

Kathleen Weidner Zoehfeld

A Shot in the Arm: Big Ideas that Changed the World #3

Don Brown

From Here to There: Inventions That Changed the Way the World Moves

Vivian Kirkfield

Glasses: Eureka! The Biography of an Idea

Lori Haskins Houran

Engineering

Engineering is prominent in the list, with familiar projects conducted in innovative ways.

Uma Wimple Charts Her House

Reif Larsen

Maxine Greatest Garden Ever

Ruth Spiro

Someone Builds the Dream

Lisa Wheeler

Mimic Makers: Biomimicry Inventors Inspired by Nature

Kristen Nordstrom

Mathematics

And mathematics is not a tool but a science in itself.

Look, Grandma! Ni, Elisi!

Art Coulson

Molly and the Mathematical Mysteries: Ten Interactive Adventures in Mathematical Wonderland

Eugenia Cheng

Luna's Yum Yum Dim Sum

Natasha Yim

Computer Science

Coding becomes science, too.

Artificial Intelligence

Dinah Williams

Coding as STEM

Coding is both language and science in more award-winning books.

What Is Nintendo?

Gina Shaw

Code Breaker, Spy Hunter: How Elizebeth Friedman Changed the Course of Two World Wars

Laurie Wallmark

The World Around

Societal and environmental problems become the theme for more award-winning books.

Amara and the Bats

Emma Reynolds

A Shot in the Arm: Big Ideas that Changed the World #3

Don Brown

Scene of The Crime: Tracking Down Criminals with Forensic Science

Hp Newquist

Bones Unearthed (Creepy and True #3)

Kerrie Logan Hollihan

Cougar Crossing: How Hollywood's Celebrity Cougar Helped Build a Bridge for City Wildlife

Meeg Pincus

Upstream, Downstream: Exploring Watershed Connections

Rowena Rae

Lady Bird Johnson, That's Who!: The Story of a Cleaner and Greener America

Tracy Nelson Maurer

Race to the Bottom of the Earth: Surviving Antarctica

Rebecca E. F. Barone

The Great Stink: How Joseph Bazalgette Solved London’s Poop Pollution Problem

Colleen Paeff

Scene of The Crime: Tracking Down Criminals with Forensic Science

Hp Newquist

Selling STEM

Invention extends to entrepreneurship.

Eat Bugs! #1: Project Startup Heather Alexander

Innovative books lead to innovative, integrated curricula. For more information on each award-winning book, go to Best STEM Books K–12 2022 | NSTA

In fall 2022, representatives from the National Science Teaching Association’s Children’s Book Council and from other disciplinary groups met for the sixth time to select exemplary children’s literature in STEM.

Since 2014 this joint committee has sought out literature that represents the best of STEM through:

- Modeling real-world innovation

- Embracing real-world design, invention, and innovation

- Connecting with authentic experiences

- Showing assimilation of new ideas

- Illustrating teamwork, diverse skills, creativity, and cooperation

- Inviting divergent thinking and doing

- Integrating interdisciplinary and creative approaches

- Exploring multiple solutions to problems

- Addressing connections between STEM disciplines

- Exploring Engineering Habits of Mind

- Systems thinking

- Creativity

- Optimization

- Collaboration

It’s important to note that the criteria above do not require science content—even if it is integrated across disciplines. The best STEM books might represent the practices of science and engineering by:

- Asking questions, solving problems, designing, and redesigning

- Integrating STEM disciplines

- Showing the progressive changes that characterize invention and/or engineering

- Demonstrating designing or redesigning, improving, building, or repairing a product or idea

- Showing the process of working through trial and error

- Progressively developing better engineering solutions

- Analyzing efforts and making necessary modifications along the way

- Illustrating that failure might happen and is acceptable — provided reflection and learning occur, including:

- Communication

- Ethical consideration

Some of these books might not cover STEM content at all. They might simply define STEM habits of mind. For example, a biography might be STEM if it shows creative thought, progressive improvement, and even struggle and failure. But just telling a sequential story of achievement in a biography would not make it a STEM book. A winner would have to provoke a sense of innovation in the reader in any genre.

All the winners are interdisciplinary in some way: Content, process, and field of endeavor. The list below attempts to classify them, but, of course, the greatest STEM achievements defy classification.

Biographies

Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Golda Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer

Traci Sorell

Building Zaha: The Story of Architect Zaha Hadid

Victoria Tentler-Krylov

A Life Electric: The Story of Nikola Tesla

Azadeh Westergaard

Benoit Mandelbrot: Reshaping the World

Robert Black

Secrets of the Sea: The Story of Jeanne Power, Revolutionary Marine Scientist

Evan Griffith

Thank You, Dr. Salk!: The Scientist Who Beat Polio and Healed the World

Dean Robbins

The Stuff Between the Stars: How Vera Rubin Discovered Most of the Universe

Sandra Nickel

Wonder Women of Science: Twelve Geniuses Who Are Currently Rocking Science, Technology, and the World

Tiera Fletcher and Ginger Rue

Inventions

Awards also were given to books about inventions and the process that multiple inventors went through.

Bicycle: Eureka! The Biography of an Idea

Lori Haskins Houran

Light Bulb: Eureka! The Biography of an Idea

Kathleen Weidner Zoehfeld

A Shot in the Arm: Big Ideas that Changed the World #3

Don Brown

From Here to There: Inventions That Changed the Way the World Moves

Vivian Kirkfield

Glasses: Eureka! The Biography of an Idea

Lori Haskins Houran

Engineering

Engineering is prominent in the list, with familiar projects conducted in innovative ways.

Uma Wimple Charts Her House

Reif Larsen

Maxine Greatest Garden Ever

Ruth Spiro

Someone Builds the Dream

Lisa Wheeler

Mimic Makers: Biomimicry Inventors Inspired by Nature

Kristen Nordstrom

Mathematics

And mathematics is not a tool but a science in itself.

Look, Grandma! Ni, Elisi!

Art Coulson

Molly and the Mathematical Mysteries: Ten Interactive Adventures in Mathematical Wonderland

Eugenia Cheng

Luna's Yum Yum Dim Sum

Natasha Yim

Computer Science

Coding becomes science, too.

Artificial Intelligence

Dinah Williams

Coding as STEM

Coding is both language and science in more award-winning books.

What Is Nintendo?

Gina Shaw

Code Breaker, Spy Hunter: How Elizebeth Friedman Changed the Course of Two World Wars

Laurie Wallmark

The World Around

Societal and environmental problems become the theme for more award-winning books.

Amara and the Bats

Emma Reynolds

A Shot in the Arm: Big Ideas that Changed the World #3

Don Brown

Scene of The Crime: Tracking Down Criminals with Forensic Science

Hp Newquist

Bones Unearthed (Creepy and True #3)

Kerrie Logan Hollihan

Cougar Crossing: How Hollywood's Celebrity Cougar Helped Build a Bridge for City Wildlife

Meeg Pincus

Upstream, Downstream: Exploring Watershed Connections

Rowena Rae

Lady Bird Johnson, That's Who!: The Story of a Cleaner and Greener America

Tracy Nelson Maurer

Race to the Bottom of the Earth: Surviving Antarctica

Rebecca E. F. Barone

The Great Stink: How Joseph Bazalgette Solved London’s Poop Pollution Problem

Colleen Paeff

Scene of The Crime: Tracking Down Criminals with Forensic Science

Hp Newquist

Selling STEM

Invention extends to entrepreneurship.

Eat Bugs! #1: Project Startup Heather Alexander

Innovative books lead to innovative, integrated curricula. For more information on each award-winning book, go to Best STEM Books K–12 2022 | NSTA

Online STEM Resources

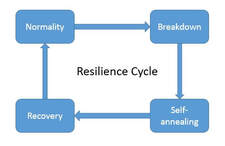

Resilient Educator is an online resource that accumulates STEAM ideas and resources for teachers. It includes current grant opportunities, research, conferences, and lesson plans. “Curricula opportunities range from taking planned STEM lessons and adding in an arts component or perspective, to developing STEAM plans that fully integrate arts education from the very start.”

STEAM Teaching Resources for Educators | Resilient Educator

Resilient Educator is an online resource that accumulates STEAM ideas and resources for teachers. It includes current grant opportunities, research, conferences, and lesson plans. “Curricula opportunities range from taking planned STEM lessons and adding in an arts component or perspective, to developing STEAM plans that fully integrate arts education from the very start.”

STEAM Teaching Resources for Educators | Resilient Educator

Celebrating Black History Month

Black History includes a great STEM star: Actalent is again celebrating Black History and STEAM with the 37th annual Black Engineer of the Year Award (BEYA) STEM Conference Celebrating Engineering Excellence - BEYA 2023 (actalentservices.com)

Black History includes a great STEM star: Actalent is again celebrating Black History and STEAM with the 37th annual Black Engineer of the Year Award (BEYA) STEM Conference Celebrating Engineering Excellence - BEYA 2023 (actalentservices.com)

NSTA Conference Features STEAM Sessions

The National Science Teaching Association meets in Atlanta beginning March 23. The program is available online, with many sessions addressing disciplinary integration such as STEAM. To find out more, visit the conference website: https://www.nsta.org/atlanta23

The National Science Teaching Association meets in Atlanta beginning March 23. The program is available online, with many sessions addressing disciplinary integration such as STEAM. To find out more, visit the conference website: https://www.nsta.org/atlanta23

Neuroscience, Creativity, and Innovation: A Collaborative Thought Leader Conversation – Part 2

11/8/2022

The Collaborative’s Research Thought Leaders help provide the strong research foundation upon which the Collaborative’s work rests. Each Thought Leader is nationally and internationally recognized in their own field and brings an extensive depth of experience and expertise. They also are adept at working across disciplines.

In our previous newsletters, we brought you interviews with each of our Thought Leaders and also examined ways to apply their important ideas in STEAM learning. This new series showcases conversations between various Thought Leaders around an important and relevant topic.

This third article in this series is Part 2 of the inspiring conversation between a leader in neuroscience, Sandi Chapman, PhD, and a leader in creativity, Bonnie Cramond, PhD. Part 1 of this conversation was published in the Collaborative’s spring, 2022 newsletter. In it, Sandi and Bonnie discussed why it is important for today’s students to develop creative (a novel idea) and innovative (applying the novel idea to solve a problem) thinking skills. In Part 2 of the conversation with Collaborative Executive Director Lucinda Presley, they discuss how to promote these thinking skills, especially though the intersections of the arts and sciences.

Sandi Chapman, PhD, a cognitive neuroscientist, is Founder and Chief Director of the University of Texas at Dallas Center for BrainHealth. She also is the Dee Wyly Distinguished University Professor in the UT Dallas School of Behavioral and Brain Sciences. She is a well-known pioneer in the field of brain health, developing brain health fitness measurements and protocols that benefit students and adults alike in the US and worldwide. (See newsletter article about her.) Bonnie Cramond, PhD, is Professor Emerita of Educational Psychology and Gifted and Creative Education at the University of Georgia (UGA) and former Director of the Torrance Center for Creativity and Talent Development at UGA. She is known for her research in the assessment and development of creativity, especially among at-risk students, and for her highly respected work in the creativity field. (See newsletter article about her.)

Are there any specific tasks you can recommend for teachers or people in general to do to promote creative and innovative thinking?

Bonnie

Empathy can be taught. To address that, I think that the Future Problem Solving Program is great. It teaches kids the steps to solve a problem. They do research, they work together in teams, and they have to learn to cooperate. Part of the process is having the students think about how others will react to the problem and their solution, which develops empathy, compassion, and especially appreciating others’ strengths.

Teachers can learn to do Future Problem Solving in any subject area. I worked with teachers in Korea who wanted to infuse creativity into science. I taught them how to use the Future Problem Solving process with their science curriculum. I couldn’t just say, “be creative”. They needed something concrete and structured. They embraced this and it really helped them. While the Future Problem Solving program is competitive, you don’t have to do the competitive program and instead can just infuse the process into your curriculum. For example, my daughter, who was in Future Problem Solving throughout her school years, used this process to teach her college students about dystopian literature. Also, there are other good programs teachers can use that give them a structure and that they can use these to teach their standards. Some examples are: The Invention Convention, Invent Now, Odyssey of the Mind, Destination Imagination, and. Dean Kamen’s FIRST Global Programs.

Sandi

One of the things that we stress for teachers is that siloed academic areas are not preparing students for the future. We have to train them how to think, integrate, and converge ideas across different areas. One way to do this is through data visualization.

In our previous newsletters, we brought you interviews with each of our Thought Leaders and also examined ways to apply their important ideas in STEAM learning. This new series showcases conversations between various Thought Leaders around an important and relevant topic.

This third article in this series is Part 2 of the inspiring conversation between a leader in neuroscience, Sandi Chapman, PhD, and a leader in creativity, Bonnie Cramond, PhD. Part 1 of this conversation was published in the Collaborative’s spring, 2022 newsletter. In it, Sandi and Bonnie discussed why it is important for today’s students to develop creative (a novel idea) and innovative (applying the novel idea to solve a problem) thinking skills. In Part 2 of the conversation with Collaborative Executive Director Lucinda Presley, they discuss how to promote these thinking skills, especially though the intersections of the arts and sciences.