By Merrie Koester, Ph.D, Collaborative Advisory Council member and Science Teacher Educator and STEAM Curriculum Specialist, University of South Carolina, Center for Science Education I am a science educator, practicing visual artist, and novelist who has, for three decades, worked to link the complementary universes of science and art as ways of more fully knowing the world. My pedagogy – these days called STEAM - centers on the artful making of ideas, performances, and artifacts that ideally lead to a sense of aesthetic transformation, joy, and empowerment. Each lesson I create and present is crafted as story, with classes feeling a lot like process drama and at times, even like improvisational theatre. As a science educator working with STEAM curriculum, I work mostly in Charleston-area Title 1 middle and high schools serving low income, historically marginalized populations. In 2016, I started paying close attention to ever- increasing numbers of flooding events, attributed to both sea level rise and the development of salt marsh wetlands. Using ArcGIS mapping software and NOAA’s Sea Level Rise Viewer, I was able to determine that multiple Title 1 middle schools – especially those built on filled and paved wetlands - would be under water with a six-foot storm surge from a hurricane. Here was a story set in the Anthropocene epoch, in which both the human and non-human world had become degraded at the same time. There was also a backstory of both social and environmental injustice. Here was a narrative, too, in which many middle and high school Next Generation Science Standards, especially the Science and Engineering Practices and Cross-Cutting Concepts, could be folded into a “plot”, featuring students in flooding schools as resources of knowledge and flood resilience for their communities. I mapped out a phenomenon-rich curriculum as a “hero’s quest”, whose “Road of Trials” would require the mastery and application of STEM knowledge/tools and the artful making of culturally responsive flooding hazard mitigation tools. Our story would be performed as participatory action research in the community with local experts and mentors. Without hesitation, city emergency management experts, cultural leaders, school officials, professional artists, our mayor, volunteer STEM experts, and higher education thought leaders from The Citadel STEM Center and the College of Charleston all stepped up as mentors. As a result, Kids Teaching Flood Resilience was born. Over the last four years, we have reached 450 students in low-income, flood-prone neighborhoods, provided capacity-building training for 41 teachers and administrators in 5 schools, and been recognized as a NOAA Weather Ready Ambassador program of excellence.

0 Comments

The dramatic change in work- and lifestyle caused by our response to COVID has given us new perspective on technology. Most of this quarter’s best professional development is online. This format challenges us to find new ways to share what we learn. Here are some options to begin your exploration of digital teaching resources that provide opportunities for STEAM teaching and learning. Take the time to read a blog Darice provides a succinct summary of ten diverse and interesting sites that show a variety of perspectives on STEAM. (Go to Blogs). One unique site from the Royal Society of Chemistry (Go to RSC) includes interesting activities to enhance our appreciation of the natural world. Go somewhere virtually! Take a virtual tour of a museum or gallery. The National Gallery of Art offers a walkthrough of fashions across the ages. The guide to the Chicago Field Museum is Sue, the famous T Rex. There are many other great galleries through which you can take a virtual stroll. These can be the core of great STEAM lessons (Go to Galleries). Explore a lesson

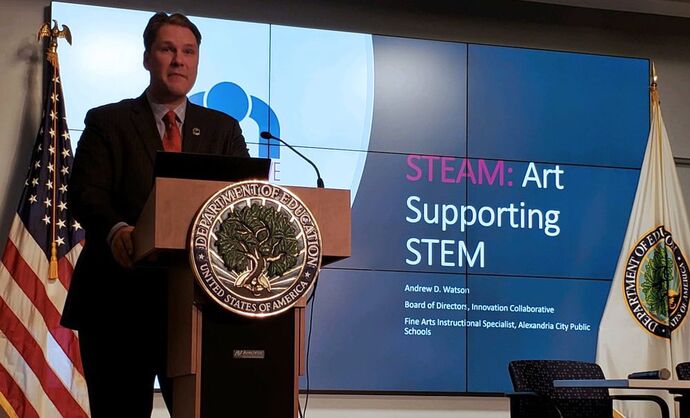

The popular hobby of model railroads involves the mathematics of quantity and scale, engineering, geography, and topography, as well as the sociology of public transportation. Underpinning the design challenge of trains is also the engineering of bridges, trestles, and tracks. A unique interdisciplinary approach to STEAM through model railroading is described in a model railroad blog: (Go to Model Railroad Blog). National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) offers design challenges for musical instruments (Go to Musical Instruments Design Challenge). It also offers challenges for “Design Bots” (Go to Design Bots Challenge). Attend virtual conferences Having withdrawal syndrome from the lack of in-person professional development? Virtual conferences are becoming more common, offering a rich variety of contacts: The U.S. Department of Education conducted a live briefing on STEAM in January, 2020. It can be seen here: (Go to U. S. Dept. of Education STEAM Briefing). (See a summary in the blog here). The presentation sparked some lively comments and criticisms. Review them here: (Go to Comments). OLC Innovate, a conference designed to challenge teaching and learning paradigms and reimagine learner experiences has been moved from July 21-24 in Chicago to an online format (Go to OLC Innovate).  Christi Wilkins, Executive Director of Dramatic Results, Gabriel Gaete from the Long Beach, California, Public Library, and Andrew Watson, member of the Innovation Collaborative Board of Directors, led a panel presentation on developing community partnerships to a group of approximately 40 leading arts education administrators and advocates at the Arts Education Partnership’s annual convening in Fall, 2019. The presentation, Systemically STEAM: Tips for Forming a STEAM Ecosystems, discussed how organizations in Long Beach, California, and Fairfax, Virginia, leveraged cultural, economic, and educational institutions to support STEAM learning in their communities. Andrew shared how teachers built a grassroots STEAM movement in Northern Virginia and how they eventually built an ecosystem around an education hub. Christi and her teammate, Gabriel Gaete, discussed how they collaborated to build a Saturday and summer learning program to engage students who were gifted, but low-income. They also shared a STEAM Ecosystem Mapping Tool created with the help of Dr. Stacie Powers from Philiber Research and Evaluation to help other organizations build their own STEAM Ecosystems.

In January, 2020, the Innovation Collaborative and collaborative partner the Arts Education Partnership were invited to present on STEAM education at the U.S. Department of Education’s STEM Briefings. Mary Dell’Erba, Senior Project Manager at the Arts Education Partnership, presented on the policy landscape of STEAM education and what is happening in states and districts across the nation. Andrew Watson, Innovation Collaborative Board member, presented on how the arts support the goals of STEM, and how the Innovation Collaborative is supporting research into STEAM education. He also shared some highlights of student STEAM work. Afterwards, they were joined by Bonnie Carter, Group Leader of Arts in Education at the U.S. Department of Education, for questions from the audience.

The presentation can be seen at: https://edstream.ed.gov/webcast/Play/9243fb2144144203b977cae26a7a3f751d  By Julie Olson, Collaborative STEM Innovation Fellow and award-winning science teacher at Mitchell Senior High/Secondary High School, Chance,South Dakota What started out as an idea for our Physic Photo Contest turned into a full- blown, very engaging STEAM learning experience for several at-risk science students. The photo contest, in itself, is a great STEAM project in which students explain the science behind a natural or contrived photograph. Here’s how the project worked with my students: A student chose to photograph and explain the hydro dipping process using a plastic soda bottle. The basic hydro dipping process involves putting spray paint on the top of a tub of water, swirling it with a stick, then dipping an object into the water. Choosing the colors, the amount of stirring affect the process. As I wanted to capitalize on a teachable moment, I explained the science behind hydro dipping. That explanation prompted me to start thinking how I could make deep connections, excite my students about learning, and develop a great STEAM unit. The next day, I discussed hydro dipping with some students who were not very excited about their Chemistry lesson. We talked about the basics of the process: a non-polar (molecules do not have a charge) substance such as paint is floating on water that is polar (molecules have a charge). The paint floats because of the density, and unlike substances, do not mix. Working together, we produced a couple of swirled plastic bottles. One student added to the conversation by noting that he had a motorcycle helmet “dipped” but with a skull design! The questions started flowing. How was that done? What did they use? The fire had been lit! We investigated and found that, in commercial processes, there are special paper and inks used to print designs. What was the cost? What kind of ink? What was the paper coated with? So, yes – more questions and thus ensuing investigations to do. The lesson depended upon having printers available that used pigment-based inks instead of dye-based. The dye-based inks are water soluble and would bleed as well as focus the color. Pigment-based inks are water insoluble and reflect light. Photography uses pigment-based inks, while most ink-jet printers use the dye water-soluble inks. The paper was then coated in PVA (polyvinyl alcohol), which is a component of glue as well as hairspray. It is water soluble. So, our investigation began as we had to find out how to create a PVA film and what to place it on. Just trying a variety of papers (e.g. wax, parchment, cardstock, foil, and plastic bags) and PVA sources (e.g. hair spray, white glue, and wood glue) was a great exploration into materials. We have now created some films and students have drawn preliminary designs on paper to later transfer it to the PVA film. But there are still intriguing questions to answer: How long does the film has to float on the water? How hot does it need to be? What is the fixative? These questions and subsequent investigations are fueling the students’ desire to learn as well as giving them a personal connection to that learning through the creation of a work of art. This is a STEAM lesson that other teachers could easily adapt for their own science and/or visual arts students. I know that it is a lesson that I will definitely repeat my students! From the Field

Everyone has been impacted by the new COVID-19 reality. Teachers, especially, have been impacted, as they have had to develop new and effective ways to continue to work with their students. One of the Collaborative’s current online STEAM teacher professionals, Ronda Sternhagen, has demonstrated how Collaborative thinking skills are useful for schools as they adapt to this new reality. Ms. Sternhagen teaches grades 5-12 visual art at Grundy Center Middle School and High School in Grundy Center, Iowa. Define the problem. School districts are trying to figure out how to deliver content to their students. Questions like, who has Internet access and who does not? Who has a device to access online content and who does not? There are more questions than answers right now but the first step is to identify all the challenges. Change perspectives. One has to ask themselves, "Is this truly something that I have to leave my home for?" Do I really need to run to town for one or two items or can I wait? This involves changing perspectives from supply needs to health needs. Collaborate. The coming together of teachers and other community members to make masks and donate them to first-responders is a great example. Create. For instance, in my community, we are creating virtual choirs and with teachers and a staff video for our students Communicate. While educators try to find new and innovative ways to communicate with their students, teachers are also finding new ways to communicate with one another. In my case, being in a rural district with about 400 students in the 5-12 grade building, staff is close - you know everyone. A group of us now have a scheduled Google Hangout every Monday and Thursday night at 9:00 pm just to chat, hang out, find out what everyone is doing, how our own families are getting along, etc. These are just a few creative ways that we’re adapting to our current situation in my community. How are you using your creative and innovative thinking skills in adjusting to COVID-19? Thanks in part to support from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Collaborative is conducting the third phase of its STEAM teacher professional development effective practices study. In its two previous studies conducted during the 2017-18 and 2018-19 school years, it discovered some important effective practices in STEAM professional development. In the 2019-20 study, it is investigating the best forms of disseminating these effective practices.

To do that, it is comparing a hybrid professional development consisting of in-person and virtual training versus completely virtual training. It also is examining the most effective practices in each of these modes of delivery. Helping lead this project are the Collaborative’s researcher, Bess Wilson, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Department of Foundations and Secondary Education, University of North Florida; Lucinda Presley, Collaborative Executive Director; the Collaborative’s Innovation Fellows, the top 10 teachers identified in the first round of research; and a number of their school administrators. They represent K-12 from the following states: Florida, Iowa, New Hampshire, North Carolina, South Dakota, and Texas. These Collaborative staff, Fellows, and administrators met virtually and then in person in Houston, Texas in November 2019. There, the Fellows helped Dr. Wilson and Ms. Presley train the administrators in STEAM intersections using discussions, in addition to hands-on and creating activities. The group then planned the teacher and administration professional development dissemination models and methods for implementation in spring semester, 2020. During this semester, there has been success in the hybrid training. Additionally, an online teacher professional development platform was developed and select teachers and administrators were invited to participate. While a limited request was sent out, the response was overwhelming. Due to limited capacity, 67 of the teachers and administrators who applied were accepted. They hail from various states, all grade levels, and a wide variety of disciplines. These disciplines include: all visual and performing arts, science, technology, engineering, math, social studies, special education, and English as a second language. These teachers and administrators have learned about the Collaborative, what STEAM is, the Collaborative’s thinking skills and its continuum of STEAM integration. After learning about the Collaborative’s rubrics and assessment, the plan was for the teachers to implement and use the rubrics to assess one the Collaborative’s top 10 lessons and a STEAM experience they created. To adapt to the wide variety of schools’ responses to the coronavirus, adjustments were made that allowed teachers and administrators to accomplish this choosing from a variety of options from the Collaborative. They also worked together to develop further creative means of implementation. Highest praise goes to the teachers and administrators who persisted, in spite of overwhelming odds, and are completing the course. They also were given resources, learned how to extend their learning, and received STEAM credentialing as a STEAM professional.  By Dr. Hope E. Wilson, Collaborative Board member and researcher, and Assistant Professor, Department of Foundations and Secondary Education, University of North Florida As the Innovation Collaborative worked to promote highly effective practices for STEAM education, it became apparent that we needed a way to measure the impact of these practices on students. As a result of this work, 4 different rubrics were developed. The background of the research can be read in this article about the rubrics. Wilson, H. E., & Presley, L. (2019). Assessing creative productivity. Gifted and Talented International, 31(4), https://doi.org/10.1080/15332276.2019.1690956 In this article, we will give you a brief overview of how you might be able to use these rubrics in your own practice as an educator, administrator, or STEM, humanities, or arts advocate. Lesson Rubrics The first set of rubrics is designed to help teachers evaluate their lessons. In these rubrics, teachers and evaluators can assess the extent to which a lesson provides opportunities for students to either integrate STEAM content and/or exhibit thinking skills. They include the Content Lesson Rubric and the Thinking Skills Lesson Rubric. Student Product Rubrics The second set of rubrics is designed to help teachers evaluate student products. In these rubrics, teachers and evaluators can assess the extent to which students either integrate STEAM content and/or exhibit thinking skills. They include the Content Student Product Rubric and the Thinking Skills Student Product Rubric. Content Rubrics Now, let's take a deeper dive into the specifics of each rubric, starting with the content rubrics. The content rubrics (for lessons or for student products) are meant to measure the extent to which the lesson or the student product demonstrates the content areas. There are three components to each of the content rubrics: Degree of Integration, STEM Content, and Arts or Humanities Content. Degree of Integration The degree of integration criterion is based upon the continuum of integration. The scale measures from low levels of integration (single disciplinary) to complex and deep integration (transdisciplinary).Think about how much the lesson offers opportunities for students to connect content areas together and how much the content areas depend on each other for the lesson to be successful. For student projects, you are evaluating how much the students are able to integrate the different disciplines together. STEM Content The STEM content criterion is based upon the quality of the science, technology, engineering, or mathematics content. This scale measures from surface-level understanding to deep, rich understanding of big ideas. This can be evaluated for how the lesson developed opportunities for understanding or for how the student demonstrated the understandings. Arts or Humanities Content The Arts or Humanities content criterion is very similar to the STEM content criterion. You will be measuring how well the lesson elicits this understanding or how well the student is able to demonstrate this understanding. You also may be assessing the students' skills or performance. Thinking Skills The next set of rubrics are based upon the thinking skills that were developed by representatives from Collaborative arts, STEM, and humanities institutions, with guidance by its Research Thought Leaders, top researchers in each field. Each of the rubrics (for lessons and for student products) have 6 criteria: Synthesis and Transformation, Generalizations and Applications, Problem Solving, Visual Analysis, Persistence, and Collaboration. Synthesis and Transformation This criterion is where the rubric captures the creativity of the student products or the ability of the lesson to elicit creativity from students. Depending on the project, you might be thinking about fluency (the number of ideas generated), originality (how unique the ideas are), relevancy (if the solution or product solves the problem in an innovative way), imagination or fancifulness (creative solutions that might not be practical), or synthesis (putting different ideas together to make a new idea). Generalizations and Applications In this section of the rubric, you are evaluating the lesson on how it gives opportunities for students to make generalizations or applications, or how well the students are able to apply their knowledge. These ideas are related to analysis of problems and ideas, scientific practices, inferencing strategies in reading and science, and examples in mathematics. Students with the highest scores in these categories will be able to make generalizations and applications that show both deep understandings and unique ways of thinking. Similarly, lessons that score highly in this category will provide open-ended opportunities for applications and generalizations, with multiple ways for students to respond. Problem Solving The problem-solving criteria refers to any (and all) of the stages of all manners of problem solving, such as engineering, artistic, and creative problem solving. Although STEAM lessons at times may not use the entire process (from asking questions to evaluating the solution), framing the lesson around portions of the process can be helpful to demonstrate the thinking skills that students are using in the lessons. For example, students may be provided opportunities to define the problem or assignment, when given looser parameters, or evaluating possible solutions if they brainstorm ideas before selecting their final project (e.g., making thumbnail sketches in art). Visual Analysis Visual Analysis refers to the process of looking, observing, and analyzing objects, materials, or other resources to gain information. This is a process that can be used in science (e.g., observations done in laboratory settings), engineering (e.g., form follows function), dance (e.g., the movement of the body), and is an important component of the STEAM curriculum. You will evaluate both the lesson's opportunities for visual analysis and the students' use of the visual analysis skills. Persistence Persistence is the ability of a student, or group of students, to continue when they face challenges, setbacks, or sense failure. High-quality lessons provide opportunities for students to experience setbacks and also to provide structure and support for students to continue. The most successful students are able to learn from their mistakes and setbacks and continue moving forward. Collaboration The last criterion involves collaboration. Through our research, we have found that collaboration has been an integral part of student success in STEAM activities. The most successful lessons involve giving students opportunities to collaborate, either in the creation of products, the generation of ideas, or the evaluations of final products. Students who are able to successfully collaborate with peers demonstrate high levels of thinking skills. A Few Notes It is not expected that every lesson or every student product would demonstrate all of the listed criterion. That would make planning a lesson almost impossible! However, we do know that the most successful lessons that engage the students the most in STEAM activities incorporate many of these criteria. We hope that the rubrics are helpful to you, not only in evaluation and assessment of lessons, but also as reflection and planning experiences for your students. Hopefully, they can help you as you think about STEAM lessons in your own classroom or school contexts.  The Collaborative’s Research Thought Leaders help provide the strong foundation upon which the Collaborative’s work rests. Each Thought Leader is nationally and internationally recognized in their own field and brings an extensive depth of experience and expertise. They also are adept at working across disciplines. A Thought Leader is featured in each Collaborative newsletter. In this issue, we visit with Bonnie Cramond, Ph.D. Bonnie is Professor Emerita of Educational Psychology and Gifted and Creative Education at the University of Georgia (UGA) and the former Director of the Torrance Center for Creativity and Talent Development at UGA. She is known for her research in the assessment and development of creativity, especially among at-risk students, and for her extensive work in the creativity field. In a conversation with Collaborative Executive Director Lucinda Presley, Bonnie talked about her work and its relationship to the Collaborative, in addition to personal reflections on her mentor, Dr. Paul Torrance. Paul Torrance was an educational psychology professor at the University of Georgia and is called “the father of creativity.” He is known for developing the Torrance Test for Creative Thinking, which is the benchmark for assessing creativity. Tell us about your career in creativity, Dr. Torrance, and the Torrance Center. I got interested in creativity while teaching 5th grade students at Woodland West in Jefferson Parish, outside of New Orleans. I was inspired by how they “took off” when I did creative things with them. For example, they were inspired by the Guinness Book of World Records to create their own Woodland West Book of School Records. They created their own categories, such as who could say the alphabet backwards the fastest. They organized school competitions, wrote up the findings, and were able to get it published for the school. The school district took notice of this and then asked me to teach gifted students. Though there were no requirements for this back then, I took a summer course on gifted education at the University of New Orleans and, in the course of study, fell in love with the work of Dr. Paul Torrance. I then entered the University of Georgia graduate program and studied with Dr. Torrance When I finished my Ph.D., I taught gifted education in middle school in Lafayette, Louisiana. I also taught gifted education, creativity, and educational psychology at the University of Southeastern Louisiana and at Western Illinois University. When Dr. Torrance retired, I was encouraged to apply for his position since I had studied with him extensively and was accepted. He became a great mentor for me in my teaching and research for the rest of his life. He was known for his generosity. For example, he anonymously paid for assistantships for students in his department. No one knew about this until he retired. Since he had no heirs, when he died, he even left his house to the graduate student who rented an apartment from him on the premises and who, along with me, took care of him in his later years. He left what money he had to the university and all royalties from his books and tests to the Torrance Center at the university. During this time, the Torrance Center for Creativity and Talent Development was established at the University of George (UGA). I was named the fourth director of the Center. Although I also had a full load of classes to teach at UGA, I was able to help the Center thrive. The Center focuses on research, education, and service. For research, its goal is to facilitate and cooperate in creativity research, building on Dr. Torrance’s research. Thanks to Dr. Torrance, the University of Georgia rare book library has the largest collection of resources on creativity in the world. Scholars come from all over the world to conduct research. In focusing on education, the Center trains classroom teachers worldwide in creativity education. For service, it conducts Saturday and summer programs for kids. It also hosts the Duke University Talent Identification Program (TIP) each summer and on weekends for gifted middle and high school students. How does your work at the Torrance Center relate to your research? I became interested in how creative students are perceived and accepted. I was interested in how we find creativity in kids and how we nurture it. I hope that what I discovered can help teachers and students in their classrooms. I was influenced by Dr. Torrance’s observations that many of the creative kids he worked with were like wild ponies, and that we must harness their energy and direct it in a positive way. Part of my work was driven by my concern that kids were being labeled ADHD (attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder) when they were actually highly creative. I worried that the numbers of kids on Ritalin was way too high – as high as 30% in some schools - and that many more kids were on these drugs in certain geographic areas. In one of my early papers (see resources below), I showed how the descriptions of ADHD and creativity were the same. I got kids who were in a special program for highly creative kids and ADHD kids to do the Torrance Test for Creative Thinking. I found that about 20% of the highly creative kids scored high on ADHD behaviors and that a third of ADHD kids scored high on creativity. I concluded that there are kids with both ADHD and creativity and that there also are some kids who are highly creative but are misdiagnosed. My concern was that teachers aren’t taught what creativity looks like and I wanted to help educators see that a creative student can be the class clown, marching to a different drummer. I was initially attacked for my findings, but recent psychological findings are showing the similarities between ADHD and creativity (see resources below). What have you discovered in your research that points to the importance of the Collaborative’s work? I have been to more than 40 countries talking about creativity and one of the big issues I’ve found is that when you mention creativity, people only think of art. While art involves a great deal of creativity, you also can express creativity through any human endeavor. For, creativity is looking at something in a different way, solving a problem in a new way, or expressing something in an original and evocative manner. The sciences, technology, enginering, and math (STEM) especially need creative thinking, for that is where our biggest breakthroughs come in. They often don’t see the need for creativity. That is where the Collaborative comes in. It is showing that creativity has a big place in STEM and through STEAM. In talking with a chemistry professor at UGA, I learned that STEM has trouble keeping females and minorities in the STEM pipline toward careers because they think STEM is so dry. One of the solutions, I believe, is in showing the importance of creative thinking in STEM courses early on, not just focusing on the formulas and the rules. A good example comes from astronomer Carl Sagan. In his article “Wonder and Skepticism”, he pointed out that science involves wonder – complete openness to new ideas – and skepticism - distinguishing between the right and wrong ideas. And one shouldn’t overpower the other. Professor Jason Cantarella, professor of mathematics at UGA, likens this to music. He points out that if we taught music like they teach math in schools, we would only teach the music scales and not get to play the beautiful music. Too often in academia we focus too much on the skepticism and not on the wonder, too much on the scales and not on the music. It’s the creativity that helps bring in the wonder and the “music”, and the Collaborative is helping with that. Do you think the Collaborative is moving the creativity/innovation fields forward? The Collaborative is definitelty moving these fields forward. It is helping show the important role these skills play in education and in all fields. It’s also showing how effective collaboration works with teachers, lessons, and evaluation. I don’t see anyone else doing this to this extent on a national level. And the Collaborative’s work is having a national impact that can affect all grade and content levels. How do you see the Thought Leaders and the Collaborative benefitting from their work together? In recent years, more research has come out showing how innovation comes from the juxtaposition of two fields. When you have two people with two different fields working together, it’s exponentially beneficial. I am energized by seeing what other people are doing, such as the other Thought Leaders. Also, while we are helping bring important information to teachers, we are also learning from them and from the Collaborative members. Are there any other thoughts you would like to share? I feel so honored to be a Thought Leader. To get to work with all these people has been so exciting and beneficial. I’m so impressed with this work! Resources that address Dr. Cramond’s research: Bonnie Cramond. The Relationship between Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Creativity. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED371495 Bonnie Cramond. The Coincidence of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Creativity. Attention Deficit Disorder Research-Based Decision-Making. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED388016 The Creativity of ADHD https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-creativity-of-adhd/ Learn more about Dr. Torrance.

By Lucinda Presley, Collaborative Executive Director Nationally recognized researchers, educators, businesses, in addition to research studies, point out that the United States’ future in the global economy could be significantly impacted by how well today’s students are taught to think creatively and innovatively. The foundation of the work done by the Innovation Collaborative is the promotion of these creative and innovative thinking skills in today’s students. A collaborative team of representatives from national arts, STEM, and humanities institutions developed the Collaborative’s list of these skills over a year and a half when the Collaborative was founded. These thinking skills now form the foundation of the Collaborative’s Effective Practices Rubrics that are used to assess effective practices in STEAM education in K-12 classrooms in all disciplines. They also have been studied and successfully statistically validated. They are important thinking skills that our students need from Pre-K throughout their education careers to enable them to be effective contributors to our future workforce. Interestingly, to successfully navigate the myriad and highly interconnected aspects of our lives impacted by the COVID-19 virus sweeping our nation, all of these Collaborative creative and innovative thinking skills are needed. Here are some examples of how workers and leaders can use these thinking skills to address the impact of COVID-19. Define the problem. For example, define their specific problem to solve in areas such as medical supply shortage, food shortage, and disease transmission (and each of these problems has many sub-problems to address) Evaluate all the necessary information. For example, determine which is the most important - and accurate - information to use in solving the problem Use visual thinking. For example, look at charts and graphs, especially statistical modeling, look at patients to visually assess symptoms, and also use other arts thinking skills such as persisting, envisioning (seeing a picture of the solution), thinking outside the box for solutions, and taking risks. The other art forms like movement, auditory imaging, and kinesthetic learning are just as important as visual thinking Reflect on a variety of sensory imagery. For instance, some students learn kinesthetically Change perspectives. For example, take a holistic view and switch perspectives from the medical to the economic to the social Compare/contrast. For example, use this skill to evaluate possible solutions Synthesize. For example, synthesize such aspects as the medical, the economic, the social, and the logistical Evaluate statements and respond. For example, evaluate information and respond to it appropriately Collaborate. For example, leaders are having to collaborate more than ever across governmental institutions and workers are having to collaborate across departments Create. For example, create effective solutions and then use visuals to present these in understandable formats to customers and to the public Persist. For example, no matter how exhausted or frustrated, workers and leaders in all fields are now having to persist to find solutions Communicate. For example, workers and leaders more than ever need to communicate their important information to the public in ways that not only are understandable and actionable, but also are motivational HOW ARE YOU USING THESE SKILLS IN YOUR DAILY LIFE? By supporting each other and working together to create a safe and effective resolution to these challenging times, we will emerge stronger, healthier, more mentally resilient, and more connected than ever before. The coronavirus is affecting all of us in many ways. Each of us, in our own spheres, is working to find the best solutions to deal with its impact in our work, in our personal lives, in our country, and in our world.

The Collaborative has been addressing this situation through:

Best wishes for your health, peace, and safety, Lucinda Presley Collaborative Chair/Executive Director |

|||||||